Sandy Bay

Is located beneath kunanyi/Mt Wellington beside timtumili minanya/the River Derwent.

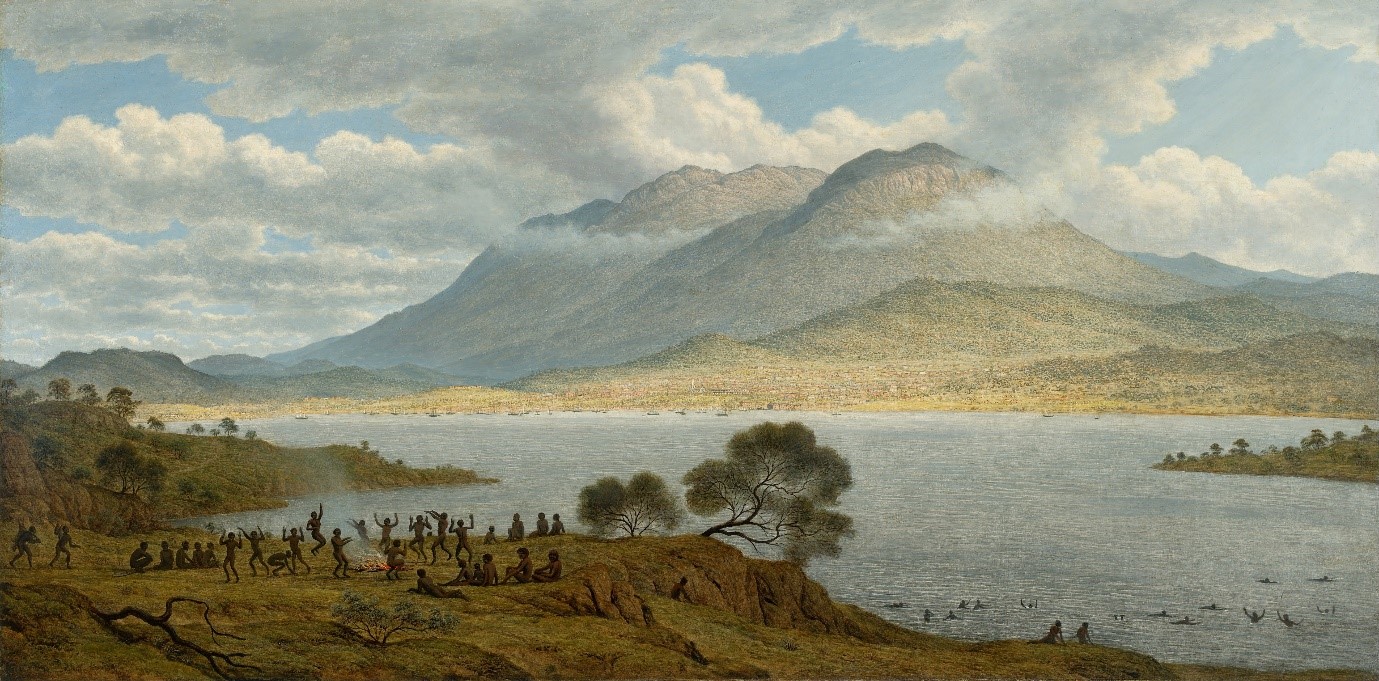

Painting by John Glover, 1834

Painting by John Glover, 1834

Environment

The area is one of hills sloping down to flatter ground along the western bank of the Derwent Estuary. Vegetation varied with terrain and altitude and consisted primarily of dry sclerophyll forest mixed with more open areas created by Aboriginal land-management practices. Many of the trees were reported to be forest giants by the invading British.

Wet sclerophyll forest and temperate rainforest occurred in the gullies and along the creeks. Sandy Bay Rivulet had its origin on the side of kunanyi; other watercourses streamed down from Mt Nelson. One ran through the Sandy Bay campus. An early colonial name for this creek was Proctor’s Road Creek. Following the establishment of a rifle range in 1870 on what is now the Sandy Bay campus (created here in the 1950s and ‘60s), the creek’s name was changed to Rifle Range Creek. The upper reaches of this creek still flow above Churchill Road (by Hytten Hall and other parts of the upper campus); but then goes under the main campus and sports ovals in a culvert. It originally flowed into a marsh where the Sandy Bay Yacht Club is located.

The diverse flora provided plants for food and raw materials to make implements, utensils, watercraft, and other things. Many of these plants are still present along Rifle Range Creek, on the hillside where the upper campus is, and even on the main campus in garden plantings of native plants.

Game was abundant and included kangaroos, wallabies, paddymelons, possums, bettongs, and bandicoots. Also, the adjacent Derwent Estuary was a highly productive marine environment, with large quantities of shellfish, crustaceans, and waterbirds(including penguins and mutton birds). Seals and whales were present. Several kelp species were available, some edible, others used for making containers. The riverside and marine resources were abundant. Taroona Point was called Crayfish Point by the British as this resource was present in large numbers.

According to Robinson (via Plomley), Woorroddy (a local Aboriginal man) told him that kreewer was the name for Little Sandy Bay and at this place was a large Aboriginal village. (the report of a large village at the Bay is significant—“village” implies a permanent community and a high population.)

John Glover painted Mount Wellington and Hobart Town from Kangaroo Point in 1834.

It is an image of mysterious, powerful nature—the large mass of Mount Wellington, looming clouds, the broad expanse of the River Derwent and the nearby open grasslands. It portrays Aboriginal people singing and dancing, fishing and swimming, at ease in the natural environment; and shows European buildings and streets, the ships, and the marching red-coated soldiers—hovering tentatively at the base of the mountain and on the edge of the water. It is an image of two worlds: the natural world of Kangaroo Point and Mount Wellington contrasted with the ‘civilised’ settlement of Hobart Town. Glover achieved success as an artist in Britain during the 1790s–1820s, painting watercolours and oils of mountains and lakes in England, Wales, Switzerland and Italy, with attention to detail, and a picturesque approach to the landscape.

Glover painted Mount Wellington and Hobart Town, during his first years in Van Diemen’s Land. He was living in Hobart in the summer of 1831–32 and was present when G.A.Robinson, brought the last of the Big River and Oyster Bay people to Government House in Hobart. Glover never saw the aboriginal people singing and dancing as he came in 1830 when most of the people had already been killed or exiled.

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/mount-wellington-and-hobart-town-from-kangaroo-point/2gG0dr7EIeS9aw

Aboriginal Presence.

In making a “camp” at “Sullivan Cove” in 1804, the British were in a place of major Aboriginal occupation. One account refers to the area from Bridgewater to Browns River as one long midden. Another refers to seeing large numbers of Aboriginal people when sailing between Hobart and Browns River in Kingston. There are frequent mentions of British hunting parties encountering Aboriginal people and Aboriginal people appearing at British establishments, sometimes in parties of hundreds.

Sources differ as to the identities of the peoples present, but there is agreement that the Derwent Estuary was a place where three nations converged: The South East, the Oyster Bay and the Big River peoples (‘Big River’ was an early colonial name for the River Ouse).

These nations consisted of an unknown number of clan groups. Two of these were the mouheneener, between Hobart and Taroona (including Sandy Bay and the UTAS Campus ), and the neunonne of Bruny Island, both part of the South East nation. Boundaries were fluid, as both nations and clans moved over the same areas (with certain protocols allowing movement onto and over other people’s countries). The Oyster Bay people on the eastern side of the Derwent and mouheneener on the west frequently crossed the river to interact with one another or gather resources. This was done by bark-bundle canoe or by using logs as swimming aids.

No historical accounts of Aboriginal people on the land of the Sandy Bay campus, have been located; however, Rifle Range Creek would have been important as it flowed into the Derwent via a large marsh, where bird life and other resources would have been abundant. There may be a midden there, which archaeological investigation may reveal.

Interaction

It is difficult to generalise about the nature of interaction between Aboriginal peoples and the invaders. At times they appear to have been quite cordial, at other times deeply conflictive. References are common to shootings, massacres (Risdon Cove being well known ), and abduction of women and girls by colonists. Cohabitation, whether by choice or not, seems to have been frequent in the early days of the colony.

The British were short of food stores during the first years at Hobart and engaged in hunting wild game on a large scale. (The colony’s Chaplain, Robert Knopwood, in his diaries does an exact accounting of the number of kangaroos and emus his convict servants shot and sold to the colonial government as food for the colonists.)

The Aboriginal land owners were not passive. There are numerous accounts of spearing and other forms of retaliation. Men were especially adept at spear throwing and also very accomplished club and rock throwers—stones were formidable weapons. Not only did they attack the invaders but also their dogs, which were vital to British hunting.

Fire

Colonial accounts make frequent reference to Aboriginal use of fire. Initially, customary Aboriginal land management practices involving fire continued, but as the British stayed longer and consumed more and more of the resources, the purpose of fires changed. They became more intense, larger and were set at different times from those associated with usual practices. For example, Knopwood notes in his diary for 13 January 1806 that the country was “on fire by the natives, with [sic] makes it very hot at Hobart town.” He also notes the burning of supplies of stored grain by Aboriginal people, and in one entry writes about going “a-kangarroing” with his gun but finding no game at all because the Aboriginal people had burned the land and driven the game away. This burning took place at the height of summer in a drought. The Aboriginal people were using fire to burn the British out (as well as starve them), and it shows the extent of Aboriginal understanding of fire. The people were knowledgeable pyro-scientists and pyro-technicians, to use Western terms.

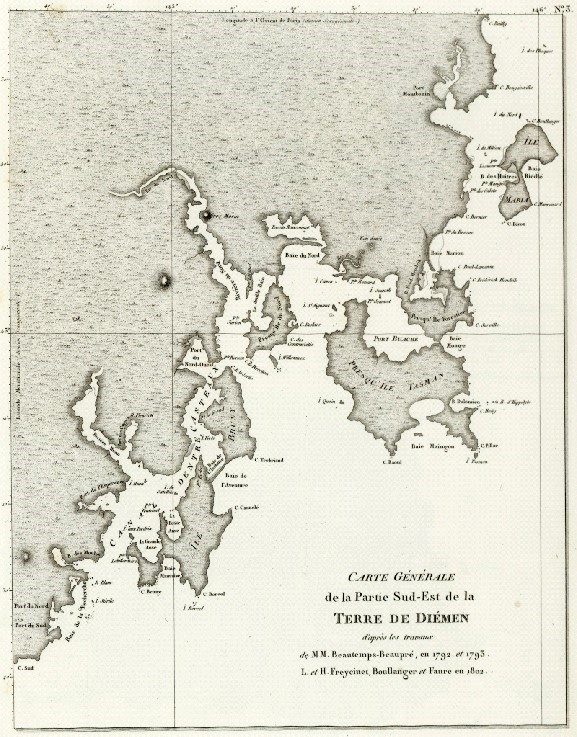

A French chart of south-eastern Tasmania. A party of Bruni d’Entrecasteaux’s men rowed up what they called the Rivière du Nord as far as Bridgewater in 1893. Nicolas Baudin’s expedition visited the area and augmented the chart in 1802.

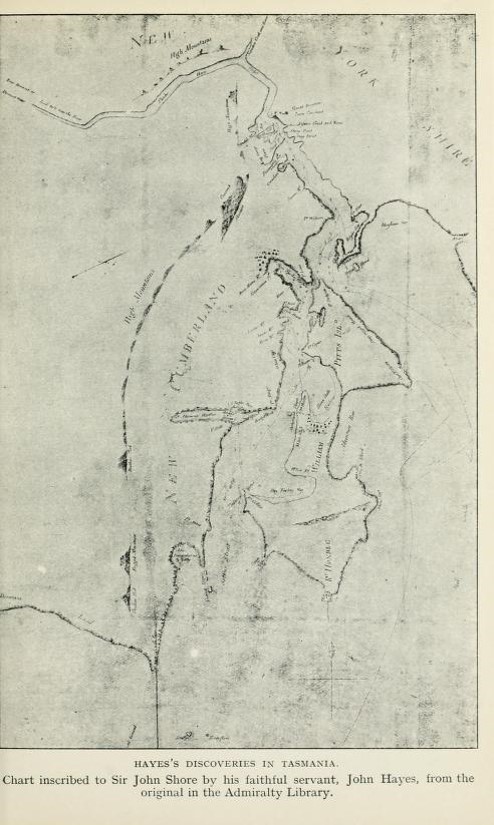

Only two months after D’Entrecasteaux’s men rowed up the Derwent, John Hayes of the British East India Company sailed his two ships up the River until it became too shallow for him to proceed. He then rowed a boat up to the vicinity of New Norfolk.

Hayes attached British names to many places along the Derwent, places that already had Aboriginal names (including the Derwent itself). This chart shows Bruni Island, which Hayes called William Pitt’s Isle; the mouth of the Derwent; a bay Hayes designated Relph’s Bay (after the captain of the second of Hayes ships - today called Ralphs Bay); a point he called Point William (today’s Sandy Bay Point); the shoreline of Sandy Bay extending northwest from Point William; Cornelian Bay; Risdon Cove (named after one of Haye’s officers); and other locations. Hayes derived the name “Derwent” from one of the English Derwent rivers.

From: Lee, Ida, 1912. Commodore Sir John Hayes: His Voyage and Life (1767–1831). London: Longmans. Facing page 20.

Available online at: https://archive.org/stream/commodoresirjohn00leei#page/n51/mode/2up (accessed 24 November 2017)