Burnie - pataway (pah-tah-why)

Photo credit: West Beach at Burnie, 1920 (AOT, PH30/1/799/4)

People have lived in Tasmania for at least 35,000 years, and possibly up to 70,000 years or longer. The area known as Emu Bay is within the territory of the plairhekenillerplue band of the North People’s Tribe. They knew the Bay as burduway, while The noeteeler band occupied the Hampshire Hills area.

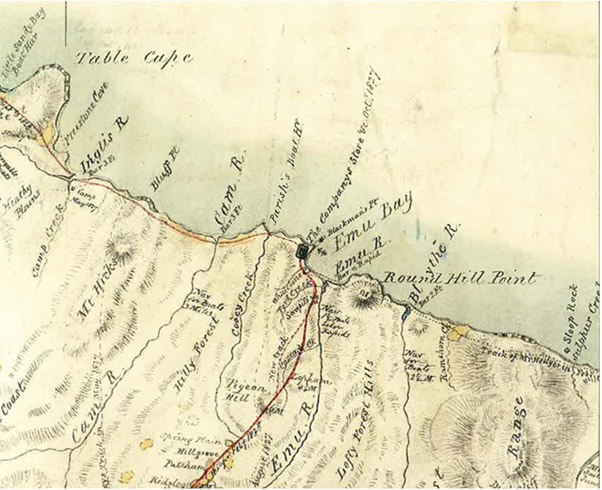

The town of Burnie, settled in 1827, was first known as Emu Bay (mutawaynatji), However, the Aboriginal name has nothing to do with ‘emus’ – white people gave this name because they saw emus on the banks of the river.

In 1830 George Augustus Robertson held the first recorded religious service in Burnie.

In 1834, after only eight years under Curr's administration, less than one sixth of the original Aboriginal inhabitants had survived to be taken into exile by Robinson’s “Friendly Mission".

Robinson's expedition provided the main link between the North West Aborigines and Arthur's administration, the primary function of the mission to the North West being to remove the remaining Aboriginal inhabitants from their tribal lands to exile on Flinders Island.

Aboriginal people were living at Circular Head and at mutawaynatji/Emu Bay. Most of the hinterland was covered with dense forest, but the high downs of the Hampshire and Surrey Hills and Middlesex Plains (south of Burnie) were favourite resorts. Other patches of open country allowed interaction with their kinsmen to the west, as well as along the coast.

Terrestrial game included kangaroos, wallabies, and wombats, as well as a range of smaller animals. Plant foods of various kinds—the roots, tubers, and seeds of rainforest and other plants—were also available, as were several edible species of fungi. The seacoast was productive and contained abundant resources, including seals and shellfish.

Inland, and along the coast, were numerous mineral deposits. Near Table Cape was an important place for obtaining wood for spears. The clay and sand from the beach was used to build the City of Burnie. Many of the early brick-built structures have not survived because the bricks were made from clay mixed with saltwater, which led the bricks to disintegrate.

Aboriginal Presence

The region including Burnie was part of the North Nation and Emu Bay/Burnie was within the country of the plairhekehillerplue people.mutawaynatji/Emu Bay was in a region of intense conflict between the Aboriginal people and the British, which makes it difficult to determine the numbers of its First Peoples.

While rainforest regions around the world tend to have low populations it was high in this area, especially along the coast and in areas where fire was used to convert rainforest to grassland or woodland (recent research shows that firestick farming allowed clearing of large areas by Indigenous peoples.

Aboriginal shell middens are distinct concentrations of shell. They contain evidence of past Aboriginal hunting; gathering; and food processing activities.

https://www.aboriginalheritage.tas.gov.au/cultural-heritage/aboriginal-shell-middens

Interaction

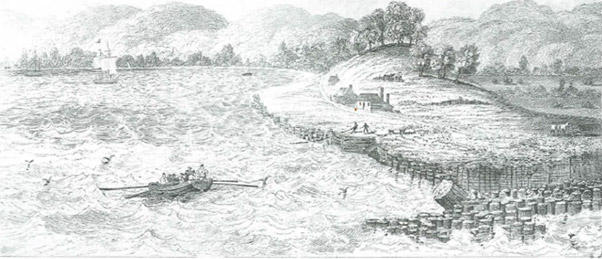

The interaction between the Aboriginal people of this area and the British cannot be considered without reference to the activities of the Van Diemen’s Land Company. The mutawaynatji /Emu Bay establishment created in 1827 was a supply port for the Company. Grazing and farming in the Hampshire and Surrey hills and at Middlesex Plains, south of mutawaynatji/Emu Bay, were more significant in the early days of the Company and are within the North nation’s country.The aim of the Company in its early years was to exterminate the Aboriginal people within the land it appropriated by Royal Charter. Conflict between Aboriginal peoples and V.D.L. employees, convict labourers working for the company and colonial settlers was intense, with several documented murders and massacres (including the Cape Grim massacre in which V.D.L workers killed a large number of men, women and children in 1828). Another incident took place at Cooee Point just west of Emu Bay. (The present UTAS Burnie campus overlooks this place.)

Pigment

The area abounds in materials for making pigments when ground up, including ochres, lead, tin, and silver. Robinson provides a vivid account of a trip to an ochre mine east of Mount Housetop in April of 1832. The Aboriginal people with him were “extremely anxious” to reach the mine. As soon as they arrived, they patted the ochre with their hands and kissed it, according to Robinson. This was probably part of a ritual, associated with arriving at an important place and taking a significant resource. The people dug up the ochre in five or six pound (2.3-2.7 km) lumps, and carried it with them when they left the next day.The Aboriginal people used these pigments for body decoration, protection from the elements and making paintings on bark sheets lining their homes. Ground lead or silver produced a shiny, and striking, image in a painting.

An extensive set of “tracks”, or Aboriginal roadways through the thick forests, were made by firing the vegetation to allow easy travel and access to these mines. These walking paths later became today’s roads.

Location of the Van Dieman’s Land Company Store